Foro Económico

Textos

seleccionados

Economic Report of the President of the USA

Together with The Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisers

March 2019

Chapter 8

Markets versus Socialism

When the Council of Economic Advisers was founded in 1946, our Nation was at a crucial crossroads. There was bipartisan concern that the transition away from a war economy would lead to another depression, and there was much public debate over the best policies to ensure prosperity. As detailed in the first CEA Annual Report to the President, there were two distinct schools of thought that Congress implicitly charged the CEA’s members to evaluate. One held “that ‘individual free enterprise’ could, through automatic processes of the market, effect the transition to full-scale peacetime business and (even with recurrent depressions) the highest practicable level of prosperity thereafter.” The other school held “that the economic activities of individuals and groups need, under modern industrial conditions, more rather than less supplementation and systemizing (though perhaps less direct regulation) by central government.” The three members of the first CEA contrasted the “Roman” view that economic prosperity can be handed down by a powerful central government with the “Spartan” view that much of American history at times “carried a cult of individual self-reliance to the point of brutality.” The report warned against “100 percenters” of both views, as each misunderstood the role of government in fostering prosperity, and it advised that “the great body of American thinking on economic matters runs toward a more balanced middle view.”

The focus of that first report reminds us that there was a time in American history when grand debates over the merits of competing economic systems were front and center, and the terms of the debates and characteristics of the competing views were widely known. It is clear that such a time may be returning. Detailed policy proposals from self-declared “socialists” are gaining support in Congress and are receiving significant public attention. Yet it is much less clear today than it was in 1946 exactly what a typical voter has in mind when he or she thinks of “socialism,” or whether those who today describe themselves as socialists would be considered “100 percenters” by the first CEA.

There is undoubtedly ample confusion concerning the meaning of the word “socialist,” but economists generally agree about how to define socialism, and they have devoted enormous time and resources to studying its costs and benefits. With an eye on this broad body of literature, this chapter discusses socialism’s historic visions and intents, its economic features, its impact on economic performance, and its relationship with recent policy proposals in the United States.

Inevitably, this chapter uses evidence to weigh in on the relative empirical merits of capitalism and socialism, a topic that can be quite divisive. In his landmark book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Joseph Schumpeter (1942, 145) predicted that socialism would become the only respectable ideology of the two, in part because the scholarship regarding both would be dominated by university professors. At the American university, he warned, capitalism “stands its trial before judges who have the sentence of death in their pockets. . . . Well, here we have numbers; a well-defined group situation of proletarian hue; and a group interest in shaping a group attitude that will much more realistically account for hostility to the capitalist order than could the theory.”

As documented in this chapter, the scholarship has not become as one-sided as Schumpeter envisioned. The chapter first briefly reviews the historical and modern socialist interpretations of market economies and the challenges socialist policy proposals face in terms of distorting incentives. Thereafter, we review the evidence from the highly socialist countries showing that they experienced sharp declines in output, especially in the industries that were taken over by the state. We review the experiences of economies with less extreme socialism and show that they also generate less output, although the shortfall is not as drastic as with the highly socialist countries. Finally, we assess the economic impact of the current American proposal for socialized medicine, “Medicare for All,” and we find that the taxes needed to finance it would reduce the size of the U.S. economy.

To economists, socialism is not a zero-one designation. Whether a country or industry is socialist is a question of the degree to which (1) the means of production, distribution, and exchange are owned or regulated by the state; and (2) the state uses its control to distribute the country’s economic output without regard for final consumers’ willingness to pay or exchange (i.e., giving resources away “for free”).1 As explained below, this definition conforms with both statements and policy proposals from leading socialists, ranging from Karl Marx to Vladimir Lenin to Mao Zedong to modern self-described socialists.2

In modern models of capitalist economies, there is, of course, an ample role for government. In particular, there are public goods and goods with externalities that will be inefficiently supplied by the free market. Public goods are undersupplied in a completely free market because there is a free-rider problem. For example, if national defense, a public good enjoyed by the whole country, were sold at local supermarkets, few would contribute because they would feel their individual purchase would not matter and they would prefer others to contribute while still being defended. Consequently, the market would not provide sufficient defense. However, socialist regimes go well beyond government intervention into markets with public goods or externalities.

This chapter is an empirical analysis of socialism that takes as its benchmark current U.S. public policies. This benchmark has the advantage of being measureable, but it necessarily differs from theoretical concepts of “capitalism” or “free markets” because the U.S. government may not limit its activity to theoretically defined public goods. Relative to the U.S. benchmark, we find that socialist public policies, though ostensibly well-intentioned, have clear opportunity costs that are directly related to the degree to which they tax and regulate.

We begin our investigation by looking closely at the most extreme socialist cases, which are Maoist China, the USSR under Lenin and Stalin, Castro’s Cuba, and other primarily agricultural countries (Pipes 2003). Referring to these same countries, Janos Kornai (1992, xxi) explained that the “development and the break-up and decline of the socialist system amount to the most important political and economic phenomena of the twentieth century. At the height of this system’s power and extent, a third of humanity lived under it.” Not long ago, distinguished economists in the U.S. and Europe offered favorable assessments of highly socialist economies, and many contemporary commentators appear to have forgotten or overlooked this record. Moreover, as one analyzes the impact of moving away from a purely socialist model, as many modern proposals envision, it may be helpful to understand the history of extreme examples.

Socialists in the highly socialist countries accused the agriculture sector of being unfair and unproductive (equivalently, food was too expensive in terms of the labor required to produce it) because farmers, who had been working on their land for generations, were too unsophisticated and because the market failed to achieve economies of scale. Government takeovers of agriculture, which forcibly converted private farms into state-owned farms directed by government employees and party apparatchiks, were advertised as the way for socialist countries to produce more food with fewer workers so resources could be shifted into other industries.

In practice, however, socialist takeovers of agriculture delivered the opposite of what was promised.3 Food production plummeted, and tens of millions of people died from starvation in the USSR, China, and other agricultural economies where the state took command. Planning the nonagricultural parts of those economies also proved impossible.

Present-day socialists do not want the dictatorship or state brutality that often coincided with the most extreme cases of socialism. However, peaceful democratic implementation of socialist policies does not eliminate the fundamental incentive and information problems created by high tax rates, large state organizations, and the centralized control of resources. Venezuela is a modern industrialized country that elected Hugo Chávez as its leader to implement socialist policies, and the result was less output in oil and other industries that were nationalized. In other words, the lessons from socialized agriculture carry over to government takeovers of oil, health insurance, and other modern industries: They produce less rather than more, even in today’s information age, where central planning is possibly easier.

Proponents of socialism acknowledge that the experiences of the USSR and other highly socialist countries are not worth repeating, but they continue to advocate increased taxation and state control. Such policies would also have negative output effects, albeit of a lesser magnitude, as are seen in crosscountry studies of the effect of greater economic freedom on real gross domestic product (GDP). A broad body of academic literature quantifies the extent of economic freedom in several dimensions, including taxation and spending, the extent of state-owned enterprises, economic regulation, and other factors. This literature finds a strong association between greater economic freedom and better economic performance, suggesting that replacing U.S. policies with highly socialist policies, such as Venezuela’s, would reduce real GDP more than 40 percent in the long run, or about $24,000 a year for the average person.

Participants in the American policy discourse sometimes cite the Nordic countries as socialist success stories. However, in many respects, the Nordic countries’ policies now differ significantly from policies that economists view as characteristic of socialism. Indeed, Nordic representatives have vehemently objected to the characterization that they are socialist (Rasmussen 2015). Nordic healthcare is not free, but rather requires substantial cost sharing. As compared with the U.S. rates at present, including implicit taxes, marginal labor income tax rates in the Nordic countries today are only somewhat greater. Nordic taxation overall is greater and is surprisingly less progressive than U.S. taxes. The Nordic countries also tax capital income less and regulate product markets less than the United States does, but they regulate labor markets more. Living standards in the Nordic countries, as measured by per capita GDP and consumption, are at least 15 percent lower than those in the United States.

With an eye toward the inaccurate description of Nordic practices, some in the U.S. have proposed nationalizing payments for healthcare—which makes up more than a sixth of the U.S. economy—through the recent “Medicare for All” proposal. This proposal would create a monopoly government health insurer to provide healthcare for “free” (i.e., without cost sharing) and to centrally set all prices paid to suppliers, such as doctors and hospitals. We find that if this policy were financed through higher taxes, GDP would fall by 9 percent, or about $7,000 per person in 2022. As shown in chapter 4 of this Report, evidence on the productivity and effectiveness of single-payer systems suggests that “Medicare for All” would reduce longevity and health, particularly among seniors, even though it would only slightly increase the fraction of the population with health insurance.4

To the extent that policy proposals mimic the 100 percent experience, the burden is on advocates to explain how their latest policy agenda would overcome the undeniable problems observed when socialist policies were tried in the past. As the sociology professor Paul Starr (2016) put it, “Much of [modern American socialists’] platform ignores the economic realities that European socialists long ago accepted.”5 Marx’s 200th birthday is a good time to gather and review the overwhelming evidence.6

The “Economics of Socialism” section of this chapter begins by briefly reviewing the historical and modern socialist interpretations of market economies and some of the challenges with socialist policy proposals. The subsequent section reviews the evidence from the highly socialist countries, by which we mean countries that were implementing the most state control of production and incomes. Highly socialist countries experienced sharp declines in output, especially in the industries that were taken over by the state. Economies with less extreme forms of socialism also generate less output, although the shortfall is not as drastic as with the highly socialist countries, as shown in the section titled “Socialism and Living Standards in a Broad Cross Section of Countries.” A section on the Nordic-countries provides a more detailed examination of them. The final section assesses the economic impact of the headline American proposal, “Medicare for All.”7

The Economics of Socialism

Historically, philosophers and even some well-regarded economists have offered socialist theories of the causes of income and wealth inequality, and they have advocated for state solutions that are commonly echoed by modern socialists. They both argue that there is “exploitation” in the market sector and there are virtually unlimited economies of scale in the public sector. Profits are undeserved and unnecessarily add to the costs of goods and services. The solutions include single-payer systems, prohibitions of for-profit business, state-determined prices to replace the “anarchy of the market,” high tax rates (“from each according to his ability”), and public policies that hand out much of the Nation’s goods and services free of charge (“to each according to his needs”) (Gregory 2004; Marx 1875).

The Socialist Economic Narrative: Exploitation Corrected by Central Planning

When Marx was writing over 150 years ago, obviously exploitive practices were still familiar. The modern socialist view is that exploitation remains real but is somewhat hidden in the market for labor (Gurley 1976a). Much inequality arises, it is said, because market activity is a zero-sum game, with owners and workers paid according to the power they possess (or lack), rather than their marginal products. From the workers’ perspective, profits are an unwarranted cost in the production process and are reflected in an unnecessarily low level of wages. The contest over the fraction of output paid in wages, known among socialists as the “class struggle,” can take place in the political arena, in the private sector with union activity and the like, or violently with riots or revolution (Przeworksi and Sprague 1986).

As Karl Marx put it, “Modern bourgeois private property is the final and most complete expression of the system of producing and appropriating products, that is based on class antagonisms, on the exploitation of the many by the few” (Marx and Engels 1848, 24). The Chinese leader Mao Zedong, who cited Marxism as the model for his country, described “the ruthless economic exploitation and political oppression of the peasants by the landlord class” (Cotterell 2011, chap. 6). The Democratic Socialists of America, and elected officials who are affiliated with and endorsed by them, today express similar concerns that workers are harmed when the profit motive is allowed to be an important part of the economic system. 8

The French economist Thomas Piketty, whose 2014 book Capital in the 21st Century recalls Marx’s Das Kapital, asserts that inequality today is “terrifying” and that public policy can and must reduce it; wealth holders must be heavily taxed.9 Piketty (2014) concludes that the Soviet approach and other attempts to “abolish private ownership” should at least be admired for being “more logically consistent.”

Historical and contemporary socialists argue that heavy taxation need not reduce national output because a public enterprise uses its efficiency and bargaining power to achieve better outcomes. Mao touted the “superiority of large cooperatives.” He decreed that the Chinese government would be the single payer for grain, prohibiting farmers from selling their grain to any other person or business (Dikӧtter 2010).10 In describing China, the British economists Joan Robinson and Solomon Adler (1958, 3) celebrated that “the agricultural producers’ cooperatives have finally put an end to the minute fragmentation of the land.” Lenin stressed transforming “agriculture from small, backward, individual farming to large-scale, advanced, collective agriculture, to joint cultivation of the land.” Proponents of socialism in America today argue that the Federal government can run healthcare more efficiently than many competing private enterprises.11

State ownership of the means of production is an often-repeated Marxist proposal for ending worker exploitation by leveraging scale economies. This aspect of socialism is less visible in modern American socialism, because in most instances, socialists would allow individuals to be the legal owners of capital and their own labor.12 However, the economic significance of ownership is control over the use of an asset and of the income it generates, rather than the legal title by itself. In other words, the economic value of ownership is sharply diminished if the legal owner has little control and little of the income.13 Full ownership in the economic sense is rejected by socialists; they maintain that private owners left to themselves would not achieve full economies of scale and would continue exploiting workers. Public monopolies, “public options,” profit prohibitions, and the regulatory apparatus allow the socialist state to control asset use, and high tax rates allow the state to determine how much income everyone receives, without necessarily abolishing ownership in the narrow legal sense.

Historical socialists—such as Lenin, Mao, and Castro—ran their countries without democracy and civil liberties. Modern democratic socialists are different in these important ways. Nevertheless, even when socialist policies are peacefully implemented under the auspices of democracy, economics has much to say about their effects.

The Role of Incentives in Raising and Spending Money

Any productive economic system needs incentives: means of motivating effort, useful application of knowledge, and the creation and maintenance of productive assets. The higher an economy’s tax rates, the more its industries are monopolized by a public enterprise, and the more its goods and services are distributed free of charge, then the more disincentives reduce the value created in the economy. Mancur Olson’s famous 1965 book The Logic of Collective Action showed how large groups have trouble achieving common goals without individual incentives. As an important example, Olson disputed Marx’s claim that business owners were working together to reduce wages, even though Olson acknowledged that business owners would have greater profits if wages were lower. The paradox, Olson said, is that the market wage is the result of a great many employers’ individual actions. Any specific employer decides the wage and working conditions to offer based on its own profits, without valuing the effects of its decision on the profits of competing employers. The result of competition among employers is that wages are in line with worker productivity, even though wages below that would enhance the profits of employers as a group.

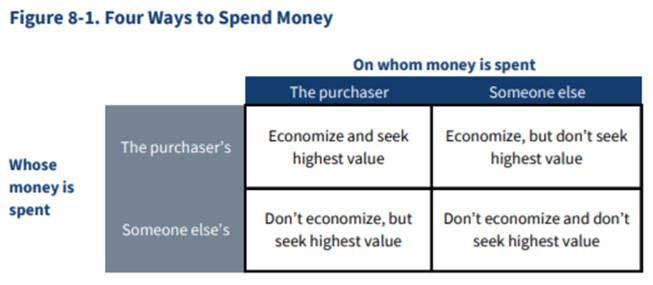

The kinds of free-rider problems analyzed by Olson are also a challenge for socialist planning, because the persons deciding on resource allocations— that is, how much to spend on a product and how that product should be manufactured and delivered to the final consumer—are different from those providing the resources and different from the final consumer who is ultimately using them. As the Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman demonstrated with his illustration of “four ways to spend money” (see figure 8-1), consumers in the market system spend their own money, and are therefore more careful how much to spend and on what the money is spent (Friedman and Friedman 1980). To the extent that they also use what they purchased—the upper left corner in figure 8-1—they are also more discerning, so that the items purchased are of good value. They will gather and consider information that helps compare the values of different options.

The upper right hand corner of figure 8-1 gives the case of spending one’s own money on someone else, which introduces inefficiencies because the recipient may place a lower value on the spending. The inefficiency of the lower left corner is exemplified by the larger spending that takes place when spending on oneself using other people’s money, as with fully reimbursed corporate travel or entertainment. The lower right category is the one applicable to government employees who spend tax revenue on government program beneficiaries; not only is there a tendency to overspend using other people’s money, but that spending may have little value from the perspective of program beneficiaries.14

Many presentations of socialist policy options, even those by expert economists, ignore the distinction between individual and group action stressed by Olson. The “Medicare for All” bills currently in Congress, for example, supposedly just swap household expenditures on health insurance that occur under a private system for household expenditures on taxes earmarked for the public program.15 But this swap fundamentally changes the types of healthcare that are ultimately received by consumers, the size of the healthcare budget, and the size of the overall economy. In a private system, a consumer has some control over his or her spending on health insurance—by, for example, selecting a plan with different benefits, or switching to a more efficient provider. Insurers in a private system must be responsive to consumer demands if they want to attract and retain customers and thus stay in business.16 Individuals also have little reason to economize on anything that they can obtain without payment (Arrow 1963; Pauly 1968).

In a socialist system, the state decides the amount to be spent, how it is spent, and when and where the services are received by the consumer. A consumer who is unhappy with the state’s choices has little recourse, especially if private businesses are prohibited from competing with the state (as they are under “Medicare for All”). It may be argued that “giant” private corporations also limit consumer choice, but this comparison ignores how corporations are subject to competition. For example, a consumer can purchase goods from Walmart rather than Amazon, not to mention a whole host of other retailers. Amazon is legally permitted to entice Walmart customers, and vice versa, with low prices, better products, free shipping, and so on. Whereas retail customers are not forced to open their wallets, giant state enterprises are guaranteed revenue through taxation and are often legally protected from competition.17 Those who maintain that Amazon and Walmart are too large might note that the single-payer revenues proposed in “Medicare for All” will be about eight times the revenue for either of these corporations.18

Another problem with the socialist system is that “other people’s money” starts to disappear when the “other people” realize that they have little incentive to earn and innovate because what they receive has little to do with how much they make.19 An important reason that people work and put forth effort is to obtain goods and services that they want. Under socialism, the things they want may be unavailable because the market no longer exists, or are made available without the need for working.

Noneconomists sometimes claim that high taxes do not prevent anyone from working, as long as the tax rate is less than 100 percent, because everyone strives to have more income rather than less. This “income maximization” hypothesis is contradicted by the most basic labor market observations, not to mention decades of research.20 Earning additional income requires sacrifices (a loss of free time, relocating to an area with better-paying jobs, training, taking an inconvenient schedule, etc.), and people evaluate whether the net income earned is enough to justify the sacrifices. Socialism’s high tax rates fundamentally tilt this trade-off in favor of less income.

The Economic Consequences of “Free” Goods and Services

Because market prices reveal economically important information about costs and consumer wants, regulations and spending programs that distribute goods or services at below-market prices, such as those that are “free,” have a number of unintended consequences (Hayek 1945). Fewer goods and services will be produced, and what is produced may be misallocated to consumers with comparatively little need. We explain in this section why the very idea that a single-payer government program will use its market power to obtain lower prices is an acknowledgment that the program will be purchasing less quantity or quality.

On the demand side of a market, people vary in their willingness to pay for the product or service, and their willingness varies over time. The market system allocates the available goods to consumers who are willing to pay more than the market price, while those not willing to pay the price go without. Willingness to pay is related to income, but it is also related to “need,” at least as consumers perceive need. Consumers are, for example, willing to pay more for food when they are hungry and to buy health insurance when they are older. In this way, the market has a tendency to allocate goods and services when and to whom they are needed.

If the government decrees that a product shall be free, then something other than a willingness to pay the market price will determine who receives the available supply. It may be a willingness to wait in line, or political connections, or membership in a privileged demographic group, or a government eligibility formula (Shleifer and Vishny 1992; Barzel 1997; Glaeser and Luttmer 2003). By comparison with the market, giving a product away for free may sometimes have the effect of taking the good away from consumers when they need it most and transferring it to consumers when they need it least. As we show in chapter 4 of this Report, single-payer healthcare programs tend to reallocate healthcare from the old to the young. Centrally planned agricultural systems have, in effect, taken food products away from starving people in rural areas and transferred the products to urban consumers or sold them on the international market.

Prices that are below their competitive levels also affect supply. Although a single government payer has market power that it can use to reduce the incomes of suppliers, the price reduction is accomplished by reducing the quantity or quality of what it purchases in order to squeeze its suppliers.21 This may be one reason why single-payer healthcare systems have longer appointment waiting times than in the U.S. system (see chapter 4 of this Report), and why “free” Nordic colleges yield lower financial returns than higher education in the United States, even though the Nordic returns include no tuition expense (see the Nordic section below).

Von Mises (1920) and Hayek (1945) emphasized the value of market prices for coordinating and executing decisions in complex economies and went so far as to assert that central planning is impossible because it eschews markets. Perhaps contrary to their expectations, centrally planned economies did survive for decades, although these economies performed poorly and survived so long only because of their deviations from the socialist program (Gregory 2004, 5–6).

Socialism’s Track Record

Socialism is a continuum. No country has zero state ownership, zero regulation, and zero taxes. Even the most highly socialist countries have retained elements of private property, with consumers sometimes spending their own money on themselves (Pryor 1992). This chapter therefore begins with the historically common highly socialist regimes, by which we mean countries that implemented the most state control of production and incomes for at least a decade.22 Highly socialist policies continue “to have considerable emotional appeal throughout the world to those who believe that it offers economic progress and fairness, free of chaotic market forces” (Gregory 2004, x). Of more than a dozen countries meeting these criteria, this section emphasizes Maoist China, Castro’s Cuba, and the USSR under Lenin and Stalin, which are the subject of much scholarship, and Venezuela, which has been unusual as an industrialized economy with elements of democracy that nonetheless pursued highly socialist policies.23

Many of the highly socialist economies were agricultural, with state and collective farming systems implemented by socialist governments to achieve purported economies of scale and, pursuant to socialist ideology, to punish private landowners. Agricultural output dropped sharply when socialism was implemented, causing food shortages. Between China and the USSR, tens of millions of people starved. It took quite some time for sympathetic scholars outside the socialist countries to acknowledge that large, state-owned farms were less productive than small private ones.

The economic failures of highly socialist policies have been described at length by both survivors and scholars who have reviewed the evidence in state archives. Not only did highly socialist countries discourage the supply of effort and capital with poor incentives, but they also allocated these resources perversely because central planning made production decisions react to output and input prices in the opposite direction from those of a market economy.

Although agriculture is not a large part of the U.S. economy, present-day socialists echo the historical socialists by arguing that healthcare, education, and other sectors are unfair and unproductive, and they promise that large state organizations will deliver fairness and economies of scale. It is therefore worth acknowledging that socialist takeovers of agriculture have delivered the opposite of what was promised.

Present-day socialists do not want the dictatorship or state brutality that often coincided with the most extreme cases of socialism, and they do not propose to nationalize agriculture. However, the peaceful democratic implementation of socialist policies does not eliminate the fundamental incentive and information problems created by high tax rates, large state organizations, and the centralized control of resources. As we report at the end of this section, Venezuela is a modern industrialized country that elected Hugo Chávez as its leader to implement socialist policies, and the result was less output in oil and other industries that were nationalized.24

When evaluating the misalignment between the promises of highly socialist regimes to eliminate the misery and exploitation of the poor and the actual effects of their policies, it is instructive to look at a major guide that economists use to determine value: the revealed preference of the population—in other words, people voting with their feet. The implementation of highly socialist policies, such as in Venezuela, has been associated with high emigration rates. Perhaps more telling is that historically socialist regimes—such as the USSR, China, North Korea, and Cuba—have forcibly prevented people from leaving.

State and Collective Farming

State and collective farming (hereafter, “state farming”) is a historically common practice in highly socialist countries.25 The state acquires private farmland, and often much livestock, by force. The land is organized in large parcels, typically about one per village, as compared with the multitude of parcels in a typical village before collectivization. Villagers are required to work on the land, with the output belonging to the state. Decisions are made by government employees and party apparatchiks, who may have had little or no experience or specialized knowledge in comparison with the original landowners (Pryor 1992). These decisions include devising and implementing complex systems of production targets and quality requirements (Nolan 1988).

The socialist narrative emphasizes exploitation and class struggle, which in an agricultural economy refers to the power dynamic that determines the division of agricultural income between landlords and farm workers. State farms purport to end the exploitation by eliminating the landlords, known as kulaks in the USSR.26 Another advantage of state farms, from the socialist perspective, was economies of scale (Pryor 1992). In principle, the knowledge and techniques of the best farmer could be applied to all the land rather than the comparatively small plot that the best farmer owned.27 Capital may be easier to obtain for a larger organization. Writing about the USSR in 1929, Joseph Stalin stressed transforming “agriculture from small, backward, individual farming to large-scale, advanced, collective agriculture, to joint cultivation of the land.” Writing about China in 1958, the British economist Joan Robinson asserted that “the minute fragmentation of the land” that prevailed before collective farming was a major source of inefficiency. The family itself was sometimes criticized as operating on too small a scale; in China, household utensils were confiscated and villagers were assigned to communal kitchens for eating and food preparation (Jisheng 2012).28

Eyewitnesses tell a different story concerning the operation of state farms, and central planning more generally. In Cuba and the USSR, for example, the managers of state farms were chosen from the ranks of the Communist Party, rather than because of management skill or agricultural knowledge (Dolot 2011).29 “The state monopoly stifled incentives for increasing production,” describes a Chinese eyewitness (Jisheng 2012, 174–77). Production units sometimes had an incentive to produce less and to hoard inputs, in order to obtain more favorable allocations the next year (Gregory 1990).

Unintended Consequences

State farms reduced agricultural productivity rather than increasing it. The unwarranted faith in state farms had a doubly negative effect on agricultural output. Not only was less produced per worker, but workers were removed from agriculture, on the mistaken understanding that farming was becoming more productive (Conquest 1986) and would produce surpluses that would finance the growth of industry (Gregory 2004). For China and the USSR, both the lack of food and reliance on central planning, rather than market mechanisms, resulted in millions of deaths by starvation.

Statistics from highly socialist regimes are informative, but necessarily imprecise. Gregory (1990), Kornai (1992), and others explain how officials in these regimes deceive their superiors and the public. Refugees from the regimes may be free to talk after their escape, but they may not constitute a random sample of the populations they left and may have imperfect memories. Readers are advised that the estimates in this section are necessarily inexact.

In Cuba, the disincentives inherent in the socialist system sharply reduced agricultural production. As O’Connor (1968, 206–7), explains, “Because wage rates bore little or no relationship to labor productivity and [state farm] income, there were few incentives for workers to engage wholeheartedly in a collective effort.” Table 8-1 shows the change in agricultural production in Cuba spanning the agrarian reform period of 1959–63, when about 70 percent of farmland was nationalized (Zimbalist and Eckstein 1987). Production of livestock fell between 14 percent (fish) and 84 percent (pork). Among the major crops, production fell between 5 percent (rice) and 75 percent (malanga). The biggest crop, sugar, fell 35 percent. There was not a major Cuban famine, however, because of Soviet assistance and emigration.30

The CEA also notes that, though Cuba had a gross national income similar to that of Puerto Rico before the Cuban Revolution in the late 1950s, by 2000 the Cuban gross national income had fallen almost two-thirds relative to Puerto Rico’s.31

In the USSR, the collectivization of agriculture occurred with the First Five-Year Plan, from 1928 to 1932. Horses were important for doing farm work, but their numbers fell by 47 percent, in part because nobody had much incentive to care for them when they became collective property (Conquest 1986). In the Central Asian parts of the USSR, the number of cattle fell more than 75 percent, and the number of sheep more than 90 percent (Conquest 1986). Looking at official Soviet data for about 1970, Johnson and Brooks (1983) concluded that the entire program of socialist policies—“excessive centralization of the planning, control, and management of agriculture, inappropriate price policies, and defective incentive systems for farm managers and workers and for enterprises that supply inputs to agriculture”—was reducing Soviet agricultural productivity about 50 percent.32

A famine ensued in 1932 and 1933, and about 6 million people died from starvation (Courtois et al. 1999).33 The death rates were high in Ukraine, a normally fertile region from which the Soviet planners had been exporting food.34 Figure 8-2 shows the time series for Ukrainian deaths by sex, along with births. This time series also appears to show that millions more people were not born because of the famine.

Mao’s government implemented the so- called Great Leap Forward for China from 1958 to 1962, including a policy of mass collectivization of agriculture that provided “no wages or cash rewards for effort” on farms.35 The per capita output of grain fell 21 percent from 1957 to 1962; for aquatic products, the drop was 31 percent; and for cotton, edible oil, and meat, it was about 55 percent (Lin 1992; Nolan 1988).36 During the Great Chinese Famine from 1959 to 1961, an estimated 45 million people died (Dikӧtter 2010). Figure 8-3 shows the time series for deaths and births, which form a pattern similar to Ukraine’s, except that the absolute number of deaths was an order of magnitude greater.

called Great Leap Forward for China from 1958 to 1962, including a policy of mass collectivization of agriculture that provided “no wages or cash rewards for effort” on farms.35 The per capita output of grain fell 21 percent from 1957 to 1962; for aquatic products, the drop was 31 percent; and for cotton, edible oil, and meat, it was about 55 percent (Lin 1992; Nolan 1988).36 During the Great Chinese Famine from 1959 to 1961, an estimated 45 million people died (Dikӧtter 2010). Figure 8-3 shows the time series for deaths and births, which form a pattern similar to Ukraine’s, except that the absolute number of deaths was an order of magnitude greater.

Failed agricultural policies are not the only way that civilians died at the hands of their highly socialist state. Rummel (1994), Courtois and others (1999), Pipes (2003), and Holmes (2009) document noncombatant deaths in the Soviet Bloc, Yugoslavia, Cuba, China, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, North Korea, and Ethiopia. These deaths exclude deaths in military combat but include deaths in purges, massacres, concentration camps, forced migration, and both escape attempts and famines. The death rate in famines was particularly high in North Korea, where about 600,000 people died from starvation in the late 1990s out of a population of about 22 million (Goodkind, West, and Johnson 2011).37 Cambodia’s Communist period was especially violent.

The total noncombatant civilian deaths in the highly socialist countries were a combination of the effects of government takeovers of important industries and brutal political systems. Modern American socialists are against state brutality. But it is a mistake to ignore the highly socialist tragedies altogether, because it was high taxes, large state organizations, and centralized control that delivered the opposite of what was promised and forced consumers to endure intolerably small supplies of food and other consumer goods. In other words, the low output of state farms and centralized planning were results of economic failures that cannot be rectified with more peaceful implementation. Venezuela, discussed below, is a case in point.

Though the nationalization of agriculture depressed output, the privatization of the same land brought it surging back. Johan Norberg explains how, when Chinese villagers began to (secretly) privatize their land, the “farmers did not start the workday when the village whistle blew any longer—they went out much earlier and worked much harder. . . . Grain output in 1979 was six times higher than the year before.”38

Although socialist policies are ostensibly implemented to reduce poverty and inequality, it was the end of highly socialist policies in China that brought these results on a worldwide scale. China’s major reforms began in 1978, which is about the time that the poverty rate in China, and therefore world poverty rates and world inequality, began a remarkable decline (Sala-i-Martin 2006).39 Policy changes in India also coincided with reduced poverty in that country, although it is debated whether the early Indian policies were socialist (Basu 2008). The end of socialism in the USSR increased poverty there, but this was not enough to offset, by worldwide measures, the progress elsewhere in the world (Pinkovskiy and Sala-i-Martin 2009).

Lessons Learned

Before the First Five-Year Plan, the USSR’s economists had observed the productivity losses that came with attempts to collectivize farming. Conquest (1986, 108) describes how they “still defended small scale agriculture in 1929—but soon had to repudiate that position.” The political leadership then prohibited the types of economic analysis that might show the opportunity costs of state farms (Conquest 1986).

Although the eyewitnesses saw in real time the economic problems with large state organizations, some distinguished economists outside the socialist countries dismissed evidence that might suggest socialism to be a failure in the USSR or China. For instance, Paul Samuelson (1976), the first American to win the Nobel Prize in economics, expressed surprise that the Soviet collective farms were not more productive than private land allotments. As recently as 1989, Samuelson and William Nordhaus (1989, 837) were still writing that “the Soviet economy is proof that, contrary to what many skeptics had earlier believed, a socialist command economy can function and even thrive.” John Gurley (1969), one of the 11 economists during the history of the American Economic Review who have served as its managing editor, wrote that “the basic overriding economic fact about China is that for twenty years it has fed, clothed, and housed everyone, has kept them healthy and has educated most. Millions have not starved.”40 As recently as 1984, John Kenneth Galbraith asserted that “the Russian system succeeds because, in contrast with the Western industrial economies, it makes full use of its manpower.”41

The infamous journalist Walter Duranty privately estimated that 7 million people died from the Soviet famine, but instead he published Soviet-censored descriptions in the New York Times during those years.42 Meanwhile, the highly socialist governments themselves eventually acknowledged the value of private enterprises. As a means of increasing national output, Cuba, China, the USSR, and other highly socialist countries eventually permitted private enterprises both in and outside the agriculture sector to coexist with state-owned enterprises.43

Central Planning in Practice

The Soviet leadership promised that “scientific planning” would replace the “chaos of the market,” whereas in practice central planning proved primitive, unreliable, and incapable of adjusting to change (Lazarev and Gregory 2003). Centralized deliveries were notoriously unreliable; managers relied on informal markets to exchange materials outside the official plan. Adding to managerial confusion and uncertainty was the fact that plans were constantly being changed based on interventions by ministry and party officials (Gregory 2004). Consumer goods were allocated based on coupon rationing or standing in line; illegal markets also proved to be more reliable for obtaining consumer goods.

Ludwig Von Mises (1990) and F. A. Hayek (1945) warned that planning an economy without prices, profit motives, and incentives is impossible. Managers in planned economies were government employees who lack incentives and even guidance to run their factories. On a more practical level, planning complexity meant that only a few commodities could be planned from the center, and then only in the form of crude aggregates like square meters of cloth or tons of steel (Zaleski 1980).

The first two five-year plans were grossly underfulfilled (Zaleski 1980). Soviet plan fulfillment improved over time, but this was not a sign of “better” planning. Rather, Soviet planners institutionalized “planning from the achieved level,” which meant that the current operational plan was almost entirely last year’s plan plus marginal adjustments (Birman 1978). Planning from the achieved level froze Soviet resource allocation in place and, curiously, created opposition to technological change as a disruptive threat to the plan.

Central planning ultimately proved to be a rather complex—and unplanned—mixture of political intervention, petty tutelage, and illegal markets (Zaleski 1980, 486; Lazarev and Gregory 2003; Gregory 2004, 189).

The Case of Venezuela Today: An Industrialized Country with Socialist Policies

Venezuela is not an agricultural economy, but in pursuing socialist policies, it nationalized important parts of its economy, implemented effectively high marginal tax rates, and centrally controlled prices of consumer and other goods. As with the other highly socialist countries, its state-owned enterprises have proven to be unproductive. Millions of people have already fled the country.

The economies of the highly socialist countries described above are agricultural and labor intensive. An oil-rich country such as Venezuela that managed its oil assets well and paid cash royalties to its citizens independent of how much they earn could in principle be providing income for its citizens with zero marginal tax rates.44 The economy could also be unregulated and without state-owned enterprises (with oil assets rented to private businesses to operate), and therefore not be socialist in any aspect of the definition introduced in the “Economics of Socialism” section above. However, this is not the path taken by Venezuela over the past 20 years, when it nationalized most oil assets and many other businesses, implemented effectively high marginal tax rates, and centrally controlled prices of consumer and other goods.

In 1999, “Hugo Chávez convinced the people of Venezuela they were being robbed by the greedy oil companies, dramatically raised taxes and royalties on new and existing projects. . . . The state-owned oil entity no longer possessed the know-how to develop its resources and production began declining” (Oil Sands Magazine 2016). Oil revenues were spent on generous social programs rather than on investing in the country’s oil production capacity or cutting taxes (Economist 2017; Monaldi 2018).45 As shown in figure 8-4, Venezuela’s oil production has been declining, while production in Canada, which has petroleum resources similar to Venezuela’s, has been increasing.46

Venezuela nationalized several other businesses, ranging from cell phones to medicines. According to Transparency International (2017, 52), “From 2001 to 2017, the Venezuelan state went from owning 74 public enterprises to 526, four times more than Brazil (130) and ten times more than Argentina,” and by 2016 state enterprise employment reached 6 percent of the entire workforce.

Earning and spending are heavily taxed in Venezuela. The top rate on personal income is 34 percent, plus 11 percent for payroll. The value-added tax rate is 16 percent. Inflation is a tax implicitly paid while a worker or consumer holds currency; even during normal times, inflation was 2 percent a month. Import restrictions are relevant because, in a well-functioning economy based on natural resources, many consumer goods would be imported. Currency transactions, and international financial transactions generally, are tightly controlled, which means that an importer would in effect pay a tax when obtaining the foreign currency required to purchase foreign goods. As of 2012, the import tariff rate was 12.1 percent on nonagricultural goods. Imports are also at risk of theft by the border patrol. If we take the foreign exchange and import theft rates to each be 10 percent, this puts the overall tax rate on earning for the purpose of obtaining consumption goods at over 60 percent (this applies a 48 percent import share to consumption).

The Venezuelan economy does not benefit from price signals in the way that less-regulated economies do. High inflation, which is expected to reach 1 million percent a year in 2018, makes it difficult to discern relative prices (Fischer, Hall, and Taylor 1981). Even without inflation, many prices are not determined by the market. In Venezuela, the 2011 Law of Fair Costs and Prices gives the Superintendency of Fair Costs and Prices (known as SUNDECOP) “broad authority to regulate the prices of almost all goods and services sold to the public,” deciding “whether prices are ‘fair’ and to identify businesses that make ‘excessive profits through speculation’” (USTR 2013). “Basic goods like flour and aspirin had fixed prices and were so cheap that companies had no incentive to make them” (Kurmanaev 2018).

Emigration has proven to be an important way in which Venezuelan policies have reduced the supply of goods and services. Talented workers have emigrated from the oil industry and from medical practices (Dube 2017). Overall, about 2 million people have emigrated from the country in recent years (Alhadeff 2018).

Economic Freedom and Living Standards in a Broad Cross Section of Countries

Of course, not all countries have pushed socialist policies to the extremes discussed in the previous section. To the extent that socialist policies would involve lesser increases in tax rates, the extensive literature on the effects of taxation could be used to assess some of the consequences of more moderate socialism, which is an approach pursued in the “Medicare for All” section of this chapter.47 But the tax literature does not address state-owned enterprises and centralized price setting, or how these practices interact with high tax rates.

An extensive economic growth literature is helpful in this regard because it documents a relationship between real GDP and the degree of socialism, measured in a large sample of countries as the opposite of economic freedom.

The studies suggest that moving U.S. policies to highly socialist policies would reduce real GDP at least 40 percent in the long run. Alternatively, adopting a 1975 Nordic level of socialism, which is about halfway toward our highly socialist benchmark of 2014 Venezuela, would reduce real GDP by at least 19 percent in the long run.48 These effects are similar to those obtained with alternative methods in the final two sections of this chapter.

The growth studies mainly rely on the Fraser Institute, which in 1996, in conjunction with 10 other economic institutes, published the book Economic Freedom of the World 1975–1995. Fraser has subsequently provided annual updates of its Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) Index, which measures the degree to which the policies and institutions of countries are supportive of economic freedom. Forty-two indicators are used to construct a summary index for each country and year that ranges between 1 for the least free and 10 for the most free. The indicators are aggregated to five main categories, which are then given equal weight in the overall index. The first category is the size of the government in terms of spending, taxation, and the size of governmentcontrolled enterprises. The second is the legal system and property rights in terms of the protection of persons having such rights. The third category is referred to as “sound money,” which measures policies related to inflation. The fourth is free international trade, which means that citizens are free to trade with other countries. And the fifth category is limited regulation, which addresses the freedom to exchange and trade domestically. Note that each category is an indicator of economic freedom, rather than political freedom or civil liberties.

Of particular interest in this chapter are the recent EFW Index values for the U.S. (8.0), the Nordic countries (averaging 7.5), and Venezuela (2.9).49 Venezuela in 2016 was one of the least free in the entire country panel.50 Also of interest is the Nordic average in 1975 (5.5), which was about when socialism peaked in those countries. In other words, the Nordic countries were once about halfway between where the U.S. and Venezuela have been recently, but now have economic freedoms that are much closer to those of the U.S.

The EFW Index is related to our discussion of more socialist policies that involve increased public financing, public production, and regulations that replace each citizen’s ability to spend his or her own money on himself or herself with the government’s spending other people’s money on others. As reviewed by Hall and Lawson (2014), the EFW Index has been cited and utilized in hundreds of academic articles. Their review discusses 402 articles, of which 198 used the EFW Index as an independent variable in an empirical study. They report that over two-thirds of these studies found economic freedom to correspond to improved types of economic performance, such as faster growth, better living standards, and more happiness, as well as other measures.

In particular, a large subliterature focuses on the correlation between the EFW Index and economic investment and growth, as reviewed by De Haan, Lundström, and Sturm (2006). One major study—by Gwartney, Holcombe, and Lawson (2006)—found that a 1-unit increase in the EFW Index from 1980 to 2000 was associated with a 2.6-percentage-point increase in private investment as a share of GDP, and thereby with a 1.2-percentage-point increase in annualized economic growth over 20 years.51 This suggests that going from the U.S. EFW level to Venezuela’s would reduce GDP by about two-thirds after 20 years.52 Going back to 1975, Nordic values of the EFW Index would reduce GDP more than 40 percent.

Another study, by Easton and Walker (1997), found effects that are smaller although still economically significant. They estimate the elasticity of the steady state level of GDP per worker with respect to the EFW Index as 0.61, so that going to Venezuela’s EFW would reduce real GDP per worker by about 40 percent in the long run.53 With the 1975 Nordic value of EFW, long-run GDP per worker would be reduced at least 19 percent. To the extent that socialism reduces the fraction of the population that works, the reductions in GDP per capita are even greater.

This evidence is suggestive as to the opportunity costs of socialism, but of course cross-country correlations are not necessarily causal. Moreover, the EFW Index is not exactly the inverse of socialism, and the various ingredients of the index can be difficult to measure. This evidence therefore needs to be considered together with the case studies in the high-socialism and Nordic sections as well as the tax-impact analysis in the “Medicare for All” section.

The Nordic Countries’ Policies and Incomes Compared with Those of the United States

The Nordic countries include Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. This section looks at these countries in more detail because they are often singled out as supposedly having socialist policies and admirable economic outcomes. Combining state, local, and central governments, public spending is about half of GDP in the Nordic countries, as compared with 38 percent of GDP in the United States (OECD 2018b). However, the Nordic countries today are hardly socialist, because they have internationally low corporate taxes, have low regulation of business, allow the private sector to participate in the provision of primary and secondary schooling, link full social benefits to having a work history, and require cost sharing for healthcare at the time of service.54 Though these countries have universal-coverage health insurance, they do not impose a single payer on the entire nation, despite being more homogeneous countries than the United States (Anell, Glenngård, and Merkur 2012; Vuorenkoski, Mladovsky, and Mossialos 2008; Olejaz et al. 2012; Ringard et al. 2013; Sigurgeirsdóttir, Waagfjörð, and Maresso 2014).55

We find that today, the Nordic countries’ marginal tax rates on labor income are not in fact far above those in the U.S., once implicit employment and income taxes are considered. The Nordic countries’ living standards are still at least 15 percent lower than those of the U.S., in large part because people work less. The private and social returns to a college education are higher in the U.S., even though college education is at least as common here. These results are consistent with the basic economic idea that redistribution and single-payer systems have significant costs in terms of reducing national incomes.

The Nordic countries themselves recognized the economic harm of high tax rates vis-à-vis creating and retaining businesses and motivating work effort, which is why their marginal tax rates on personal and corporate income have fallen 20 or 30 points, or more, from their peaks in the 1970s and 1980s (Stenkula, Johansson, and Du Rietz 2014).

Measuring Tax Policies in the Nordic Countries

The Nordic countries are reputed to have taxes that are higher but “fairer” than those in the United States. However, the Nordic-country average tax rate on capital income is lower than in the United States, even since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered the top U.S. statutory corporate tax rate by 13 percentage points.56 Nordic taxes on labor are only somewhat higher than in the United States, especially once implicit taxes are acknowledged.

A key difference between Nordic and U.S. taxation is that the former is broader based and the latter is considerably more progressive. With lower thresholds for their income tax brackets, the Nordic economies apply their highest marginal tax rate to taxpayers earning only a marginally above-average income, meaning that low- and middle-income tax filers face substantially higher average rates in the Nordic countries than in the United States. Moreover, the Nordic countries rely more heavily on value-added, or consumption, taxes, which are not progressive. The higher tax revenue share of GDP in the Nordic economies is thus predominantly accounted for by a broader base, rather than by “taxing the rich.” As shown below, Senator Bernie Sanders is currently proposing tax rates that are above the Nordic-country average in six of seven tax categories, with the exception being sales / value-added taxes.57

As shown in table 8-2, the corporate income tax rate in the Nordic countries ranges from 20 to 23 percent, which was about half the U.S. Federal and State statutory rate until 2018. Other tax rates vary significantly among the Nordic countries. The top personal rate on dividend income is 29 percent in the U.S., compared with 22 percent in Iceland, 29 percent in Finland, 30 percent in Sweden, 31 percent in Norway, and 42 percent in Denmark. Sweden and Norway have no estate tax, while the top estate tax rates range from 10 to 19 percent in the other three Nordic countries, as compared with 43 percent in the U.S.58

Senator Sanders has made specific proposals for the taxation of capital in the United States. He voted against cutting the corporate income tax, which in 2016 had the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD’s) highest combined statutory rate of about 39 percent for Federal and State taxes combined, and he now supports repealing the cut (Bollier 2018). This rate is well above where the U.S. and the Nordic countries are now. The senator has proposed a 68 percent rate on dividends and capital gains, which is more than double, or about 39 points above, where the U.S. is now.59 He has also proposed adding 24 points to the top estate tax rate, even though the U.S. rate is already well above Nordic rates.

The Nordic countries are similar to the U.S. in terms of their payroll tax rates (combined for employer and employee) and the top personal income tax rate.60 Even excluding implicit taxes, the overall top marginal tax rate on personal income in the United States in 2017, 46.3 percent (as calculated by the OECD), was only 3 percentage points below the Nordic average of about 50 percent.61 Senator Sanders also proposes increasing both payroll and personal income tax rates above the Nordic average, especially as regards the top personal rate.

None of the entries in table 8-2 incorporate implicit taxes, which refer to the loss or gain of transfer income that occurs when a household works or earns more. In the Nordic countries, implicit tax rates can be negative because working or earning more entitles a person to additional transfer income that helps offset some of the extra payroll, income, or sales tax that he or she will pay. In other words, a Nordic citizen with a history of working or earning more will receive a greater benefit when he or she has earned more in the past. For example, work is required in order to be eligible for full paid family leave, unemployment, or retirement benefits.62 As a result, the disincentive to work in a Nordic country may be somewhat less than what is shown in table 8-2.

In the U.S., working and earning does cause a program beneficiary to lose benefits, which is not the case for Nordic-country health and other benefits. In other words, U.S. programs tend to have positive implicit taxes on work because the people who work and earn more are paid fewer benefits.63 Table 8-2 shows a gap between Nordic and U.S. marginal tax rates on labor income, but the true gap would likely be smaller if implicit taxes were fully considered.

Margaret Thatcher (1976) observed that “socialism started by saying it was going to tax the rich, very rapidly it was taxing the middle income groups. Now, it’s taxing people quite highly with incomes way below.” Obtaining large amounts of tax revenue ultimately involves resorting to high tax rates on the poor and middle class because these groups in the aggregate generate much of the Nation’s income—what economists call “widening the tax base” (Becker and Mulligan 2003). Another way that the Nordic countries broadly levy high rates is with a value-added tax (VAT), which is essentially a national sales tax. Regardless of whether they are rich, poor, or in between, Nordic consumers are required to pay an additional VAT of 24 or 25 percent on their purchases, on top of all the other taxes that they pay.64 By comparison, in the U.S. sales are taxed by States rather than the Federal government, but no State has a rate much above 10 percent, and the national average sales tax rate is about 6 percent. Excise taxes and nonrecurrent taxes—which include carbon taxes and sales taxes on specific products such as gasoline, tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, and automobiles—are also higher in the Nordic countries (see the second-to-last row of table 8-2).

Even without the VAT, the high Nordic rates apply to everyone, not just high-income households. The OECD prepares a measure of progressivity that is the share of nationwide household taxes paid by the top 10 percent of citizens (ranked by their income), expressed as a ratio of the share of national aggregate income.65 The ratio would be 1 if the household taxes were a fixed proportion of income. A regressive tax would have a ratio less than 1; a progressive tax would have a ratio greater than 1. As shown in table 8-2’s last row, four of the Nordic countries have essentially proportional household taxes.66 The average progressivity of all five countries is 1.01, which is 0.34 less progressive than in the U.S.

Another indication of the progressivity of U.S. income taxation relative to the Nordic countries is the threshold, expressed as a multiple of the average wage, at which the top marginal income tax rate comes into effect.67 As shown in figure 8-5, in the United States, the top marginal rate only applies to income above 8 times the average wage. In contrast, on average, in the Nordic countries the top marginal income tax rate applies to income that is only 1.5 times the average wage. Indeed, in Denmark, earnings that are just 1.3 times the average are already subject to the top tax rate. To put this in perspective, if the U.S. tax code were as flat as that of Denmark, a filer earning just $70,000 a year (about in the middle of the household income distribution) would already face the top marginal personal income tax rate of 46.3 percent, whereas the U.S. code allows a filer to earn as much as 6 times that, or $423,904, before paying the top rate.

Lower personal income tax progressivity in the Nordic countries, combined with lower taxation on capital and, on average, only modestly higher marginal personal income tax rates on the right tail of the income distribution, means that a core feature of the Nordic tax model is higher tax rates on average and near-average income workers and their families. That is, contrary to the assertions of American proponents of Nordic-style democratic socialism, the Nordic model of taxation does not heavily rely on punitive rates on highincome households but rather on imposing high rates on households in the middle of the income distribution. This is illustrated in table 8-3, which reports that even after accounting for transfers, a one-income couple earning the average wage, with two children, faces an all-in average personal income tax rate of 22 percent in the Nordic countries (counting government transfers as a negative tax), as compared with a rate of 14.2 percent in the United States. This comparison for the various family types suggests that American families earning the average wage would be taxed $2,000 to $5,000 more a year net of transfers if the United States had current Nordic policies.

Measuring Regulation in the Nordic Countries

According to the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Index, the Nordic economies—and particularly Denmark and Sweden—are above the OECD mean with respect to regulatory freedom, while the Heritage Foundation ranks all the Nordic economies higher than the United States for business freedom (Gwartney, Lawson, and Hall 2017; Miller, Kim, and Roberts 2018). OECD data show that the Nordic countries have less regulation in their product markets and more regulation in their labor markets in comparison with the United States. The Nordic countries are fairly similar to the average OECD member country on the regulation measures.

The top rows of table 8-4 show how the OECD ranks all five Nordic countries as having less product market regulation than the United States, largely due to Nordic deregulation actions over the past 20 years. In comparison with the Nordic countries, the study finds the United States to be especially high on price controls and command-and-control regulation of business operations.68 As shown in chapter 2 of this Report, the Trump Administration has taken steps to reduce the costs of Federal regulations and to prevent the regulatory state from growing as it had in the past.

Unlike the United States, the Nordic countries do not have minimum wage laws, although the vast majority of jobs have wages limited by collective bargaining agreements. The Nordic countries have more employment protection legislation, which can make labor markets more rigid, although the Nordic economies obtain labor market flexibility with intensive use of temporary employees.69

Income and Work Comparisons with the United States

The average real GDP per capita in the United States is about 20 percent above the averages in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, and Sweden. The comparison with Norway is also similar, if we adjust for Norway’s large oil income. Indeed, Alaska and North Dakota—U.S. States that, like Norway, have high energy production per person—enjoy per capita GDP that is 15 and 4 percent higher, respectively, than Norway’s.

Adults in Denmark and Norway work about 20 percent less, and in Sweden and Finland about 10 percent less, than American adults do, while work hours are similar in Iceland and the United States. Arguably, the citizens of these countries are partly “compensated” for lower incomes in terms of having additional free time, but note that all the countries have significant taxes on labor so that the national value of free time is less than the private value.70

To begin understanding the financial consequences of living in a Nordic country rather than the U.S., consider the cost of owning and operating a Honda Civic sedan, which is one of the more popular personal vehicles in the U.S. We take the case of a standard four-door Civic, which is available in all the Nordic countries (see figure 8-6). The car’s base price in the U.S. is $20,568 (including a 5.75 percent average vehicle sales tax), as compared with $39,617 in Denmark (including the VAT and vehicle taxes). Fuel taxes, which are higher in the Nordic countries than in the U.S., also add to the cost of ownership in the Nordic countries. In Denmark, for example, personal vehicles are excise taxed at 85 percent of the sticker price for the first $30,000, and an additional 150 percent tax is added for more than $30,000. As a result, owning and operating the automobile costs Danish consumers substantially more than it costs American consumers. In the U.S., the average annual cost of owning a Honda Civic, accounting for the purchase price and fuel costs, is $4,175. The average consumer in Denmark, for example, must pay $7,874 each year to afford a Civic. The greater ownership costs in the Nordic countries reflect a combination of higher retail prices (including the VAT), higher fuel costs, and other combinations of registration and owner taxes.

Figure 8-7 extends the automobile results to all goods and services in the economy by using real income and production statistics. The blue bars show real GDP per capita in the home country relative to the average for the entire U.S.71 Four of the bars are negative, meaning that those countries have less GDP per capita. Despite being an oil-rich country, Norway’s average GDP per capita is only somewhat above the U.S. average, and is 13 percent below the average GDP per capita in the oil-rich State of Alaska (not shown in the figure).

Furthermore, it has been noted that the true U.S./Nordic output gap is likely even greater because the U.S. has more nonmarket household production, such as at-home child care or home schooling, than the Nordic countries do. Nordic countries tend to do more of their child care in the marketplace because child care is a government job. As Sherwin Rosen (1997, 82) described Sweden, “a large fraction of women work in the public sector to take care of the children of other women who work in the public sector to care for the parents of the women who are looking after their children. If Swedish women take care of each other’s parents in exchange for taking care of each other’s children, how much additional real output comes of it?”

Figure 8-7’s red bars show the per capita income of people with Nordic ancestry living in the U.S., and who therefore are not subject to Nordic tax rates and regulations.72 They have incomes of about 30 percent more than the average American and, based also on the red bars, about 50 percent more income than the average in their home country. This suggests that the incomes of Nordic people are not lower because, apart from public policy, low incomes are somehow cultural.

However, the difference between the incomes of Nordic people in the U.S. and Nordic people living in the Nordic countries is too large to be entirely due to policy differences between the two sets of countries. One contributing factor may be that ancestry is self-reported and that, holding actual ancestry constant, the propensity to identify with Nordic ancestry may be correlated with income. Another factor may be that there was positive self-selection bias among Nordic emigrants to the United States. That is, those who emigrated from the Nordic countries to the United States would be earning more than the home country average if they and their families had not emigrated.73

Another indicator of differences in material well-being in the Nordic economies and the United States is average individual consumption per head.74 Table 8-5 reports average individual consumption per head at current prices and exchange rates, adjusted for purchasing power parity, with the United States indexed to 100. In 2016, the most recent year for which data are available, average individual consumption per head was 31 percent lower in Denmark than in the United States, and 32 percent lower in Sweden than in the United States. The only Nordic economy in which average consumption is within 20 percent of the U.S. level is Norway, where average consumption per head is 82 percent of the U.S. level.

Though the Nordic economies exhibit lower output and consumption per capita, they also exhibit lower levels of relative income inequality as conventionally measured. Table 8-6 reports Gini coefficients, a standard way of measuring inequality, for disposable income after taxes and transfers in the Nordic economies and the United States in 2015. On average, the U.S. Gini coefficient is about 0.1 percentage point higher than the Nordic economies’, indicating higher relative income inequality. The Palma ratio—the ratio of disposable income at the 90th percentile to disposable income at the 50th percentile—is also higher in the United States than in the Nordic countries, as reported in table 8-6.

However, by some measures, even low-income American households have better living standards than the average person living in a Nordic country. Using 1999 data, Fredrik Bergström and Robert Gidehag (2004) found that all the States of the United States had a smaller percentage of households with incomes below $25,000 than Sweden did. As a country, the percentage was less than 30 for the United States, as compared with more than 40 for Sweden. Robert Rector and Kirk Johnson (2004) reviewed evidence from a sample of 15 European countries and found that homes were smaller for the average in all three of the sample’s Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, and Sweden) than they were for poor households in the United States. Conversely, though the OECD Gini database shows median incomes to be greater in the United States than in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, and Sweden, it shows the opposite at the 10th percentile of the income distribution.75

Returns to “Free” Higher Education in the Nordic Countries

An OECD (2018a) study of education systems reports that college tuitions are zero in Denmark, Finland, and Norway.76 Given that modern American socialists advocate free college tuition and stipends paid for by the Federal government (i.e., taxpayers), it is worth looking at the Nordic experience in this area to see whether, consistent with the economics of socialism, offering college for free (to the student) affects its quality.77

The same OECD study estimates that, though many American students pay tuition, Americans are somewhat more likely to attain tertiary (post–high school) education on average.78 In comparison with the tertiary schooling returns in the Nordic countries, American college graduates earn their tuition investment back with interest, and also a lot more. To put it another way, the rates of return to a college education in the Nordic countries are low, and propensities to invest in it are not high, despite the fact that such an investment requires no tuition payments out of pocket.

Figure 8-8’s bars, measured in U.S. dollars adjusted for purchasing power parity, show the OECD’s estimates of the possibly negative net present financial value of a college education in the four countries, for men, discounted with an 8 percent interest rate.79 The OECD’s estimates of the financial payoff to a U.S. college education are far greater, despite the fact that tuition payments count as negatives in the calculations.

The calculations are comparing two lifetime cash-flow profiles: (1) beginning work after high school and getting the earnings (after taxes) associated with that level of education; and (2) earning nothing during the college years, and paying tuition (if any), but then earning (after taxes) associated with a college education. Note that high school profile 1 has positive cash flows during the college ages, whereas college profile 2 has negative or zero cash flows according to the amount of tuition. A positive value means that investing the positive college age cash flows from the high school profile 1 at 8 percent yields less than the borrowing to pay tuition if any and then enjoying the extra earnings associated with college. A negative value, as for Norway, means that a student who could invest his or her high school earnings at 8 percent a year (real) would be financially ahead by working rather than going to college. The U.S. value of $108,700 means that the present value (discounted at 8 percent) of the college profile 2 exceeds the present value of the high school profile 1 by $108,700.80

Taxes and tuition subsidies are among the reasons that the financial value of a college education varies across countries. Their effects on the results can be removed by looking at earnings before taxes and by including public tuition subsidies as a cost. Even from this social (private plus public) perspective, the U.S. financial return is more than double the Nordic returns.81 This is consistent with the economic hypothesis advanced in the “Economics of Socialism” section above that making a good “free” reduces its quality.82

Socialized Medicine: The Case of “Medicare for All”